“As a child, I witnessed the humiliation and contempt so closely that, over time, dignity is something that concerns me to the point of obsession”.

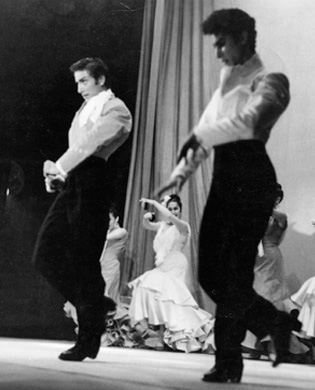

Gades recognized in Pilar López the teacher from who he’d earn the ethics of dance, which is dance the dance without seeking easy applause. A dance without deceit, without selling out, a dance where doing a dignified job means more than the ego; that is, a dance that doesn’t seek the easy way, the grandiose, to earn the audience’s adoration.

Gades used to say that he had spoiled Spanish audiences, and that there were some who hid behind the word artist to do anything. And wondered why there wasn’t also quality assurance for such an important thing as dance. He always recognized that what he danced was the culture of a people, and that this was the cornerstone of the ethics of dance: deeply studying this culture and doing things right, respecting their essence, knowing that you are representing the culture of a people. “The Jota is the Jota. Do you think adding a rock step enriches it? No, on the contrary, I think it makes it worse. If an artist is honest, he works seriously and does well, so he honors his responsibility. Responsibility is like freedom, it’s part of who you are”.

“Thanks to the ordinary and simple people who shared the inexhaustible flow of their wisdom to enrich my work. These people taught me that you have to caress the ground; some do this to coax out its wheat, we coax out its music. Stomping and humiliating it coaxes out neither music nor ears of wheat”.

The constructivist movement taught him what a pure line was, and he found a taste for perfections under its maxim that admitted no sloppiness. In this exercise he found a taste for perfection. “It seems to me it’s necessary to always do your best. Look how slow I am, I’ve only done four ballets in 40 years. It happens that I’m not out for fame, or successes, or anything”.

The ethics of dance is, for Gades, also an attitude towards public life. “I’m someone who has earned a living in silence”. He said that he wouldn’t go to heaven, that he didn’t care about heaven; what mattered was that the work was dignified and honest. “I studied hard in order to pursue my profession in the most honest way”. Gades didn’t believe in virtuosity, nor did he think he was doing art simply by stepping in front of a mirror and doing something beautiful. “I just believe in the work above all, and then it’s up to others to define it, to say if that work has art or not”.

Gades never made concessions. The applause at his shows was cut off, because his pieces were created without the traditional pauses for clapping. His conviction reached the point of saying that the greatest success for him would be to finish a flamenco dance and for the public to remain silent without applauding, simply rising at the end with the same respect that one sees inside a cathedral. That silent music, as Bergamín said, quiet music.